Let’s give credit where credit is due. Dallas County and City of Dallas public officials have not won any accolades recently for decisions regarding programs that impact the quality of life for its multicultural community.The recent fiasco surrounding the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine is the most recent example, but two other recent programs also come to mind – the Census 2020 Campaign and the lingering presence of food deserts in South Dallas. As I will argue, these programs have one important thing in common that has posed a barrier to their success: the absence of quality research to guide decisions regarding public programs that are targeted to Black and Latino residents.

In 2020, I published a book entitled “The Culture of Research” that discusses the importance of conducting sound research in culturally and linguistically diverse communities and the consequences to decision making when such studies are missing or poorly conducted. Following are some insights derived from this book that should help the reader understand how sound research with multicultural communities could have produced improved outcomes in the management of the local COVID-19 vaccination program, the Census 2020 Campaign, and solving the mystery surrounding the persistence of food deserts in South Dallas.

COVID-19 Vaccine Awareness, Registration and Distribution

The local confusion and mismanagement associated with the COVID-19 vaccine distribution can be traced originally to the absence of guidance and transparency at the federal level, and the related decision by the previous administration to allow states to define their own independent strategies with a minimal financial support from the federal government.

Nonetheless, the COVID-19 vaccine distribution dilemma in Dallas County, Texas presents a good case study on decisions that public officials in urban communities should not make. Indeed, the series of inconsistent and questionable decisions resulted in considerable public confusion and frustration with vaccine registrations, availability and distribution. Some of these missteps included the following:

- Contradictory messages from county and city public officials;

- Over-reliance on an Internet strategy to inform and register residents, many who lacked online access or own a computer, or were not comfortable with technology;

- Inconsistent support in Spanish and other languages;

- Placement of testing and vaccination sites in higher income while providing limited access in the more vulnerable areas; and

- Transportation barriers that prevented some residents to travel to testing or vaccination sites.

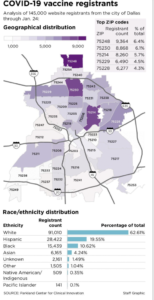

Figure 1:

Figure 1, published recently in The Dallas Morning News, clearly illustrates this pattern: [1] whites comprised 62.2 percent of all persons vaccinated while representing 28.2% of the County population; Hispanics represented 19.5 percent of those vaccinated while comprising 40.8% of the population; and Blacks comprised 10.6 percent of those vaccinated although they represented 22.3% of the county population. These disparities persist despite recent efforts by public officials to communicate more directly with civic leaders, churches and community organizations to improve vaccination rates for Blacks and Latinos in the South and Northwest part of Dallas.

The problem associated with vaccine distribution in communities of color is deeply concerning because they are the most likely to experience the more serious medical consequences from the coronavirus. Importantly, these missteps in decision making could have been avoided with communications that were better coordinated by public officials and engagement of experts with significant experience engaging multicultural persons.

The decision to use an Internet vehicle for the vaccination campaign is very likely the reason that white, higher income residents continue to be more successful in getting vaccinated. Although some public officials supported the idea of targeting zip codes in South Dallas that included some of the most vulnerable Black and Latino residents, the Texas State Health Department[2]immediately issued a threat to withhold vaccine doses allocated to Dallas County if the targeting was implemented. This threat was a direct contradiction to recommendations by the National Academy of Sciences that support vaccine community intervention programs that are targeted to the most vulnerable communities. [3] Thus, Dallas County and City of Dallas public officials learned the hard way that launching a public vaccination program in linguistically and culturally diverse communities require less reliance on technology and more reliance on outreach efforts that take the vaccines to the residents. Ironically, while the state threatened to withhold vaccine doses if local officials employed a zip-code targeting approach in South Dallas, the use of an Internet strategy as the primary form of communication accomplished the same outcome by vaccinating higher numbers of white, higher-income residents who resided in the northern parts of Dallas County.

South Dallas Food Deserts

Why have mainstream supermarkets avoided South Dallas food deserts that are populated by lower-income Blacks and Latinos? [4]This question inspired me to conduct a geospatial analysis using crime, demographic and supermarket expenditure data to examine the common reasons cited by supermarket executives to explain the avoidance of communities like South Dallas – such as high crime, low population density, lower household median income and insufficient food expenditures. The study revealed that crime patterns were often inflated by previous investigators and news stories, and that the annual food-at-home expenditures in several food deserts in South Dallas were adequate to sustain the annual sales of a mainstream supermarket. Flawed crime analyses, stereotypes of urban retail, and an apparent disdain for Black and Latino customers appeared to drive site selection decisions in South Dallas.

Over the past two decades, the City has floundered millions of taxpayer dollars on ill- conceived investments that failed to produce positive changes in the supermarket options for this community. Worst yet, a market demand study of community residents – a traditional practice to measure supermarket opportunities — has never been conducted in South Dallas. Such a study would have provided supermarket and site selection executives the statistical evidence needed for an investment decision. In the meantime, South Dallas residents will be forced to continue shopping outside of their community for healthy, affordable food or visit the less desirable dollar stores. Once City public officials decide that the South Dallas community is deserving of a high-quality supermarket experience, a professional, high quality market demand study is the best approach for making this a reality. If supermarket redlining practices continue in South Dallas despite solid evidence of its retail potential, it might be a good idea to recruit a supermarket chain from outside of Dallas County or Texas that reveals a greater interest in serving Black and Latino consumers in urban communities.

The Census 2020 Campaign

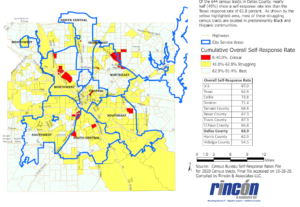

In January 2020, Dallas County and the City of Dallas funded a $1.9 million Census 2020 Campaign to provide a comprehensive strategy to boost response rates in hard-to-count communities that were populated by lower-income Blacks and Latinos. The team selected to conduct the campaign submitted a report summarizing the multitude of campaign activities that they conducted from February to August of 2020 to target these HTC communities. To monitor progress on this campaign, I produced maps on a monthly basis that illustrated the cumulative self-response rates by census tracts that were provided by the Census Bureau. Figure 2 below shows that the final self-response rates reported by the Census Bureau were decidedly lower in the southern and northwest parts of the city where HTC Blacks and Latinos resided. In fact, the table of Overall Self-Response Rates indicates that Dallas County ended with one of the lowest self-response rates (63.9%) compared to other large Texas counties. Consequently, the Census Bureau was required to deploy many more field interviewers in order to minimize the potential population under-count, an especially difficult task during the pandemic. Despite its best intentions, the Census 2020 Campaign funded by the County and City appeared to fall short of its intended goal in hard-to-count communities and will likely lead to the loss of millions of federal dollars for local programs. Although the pandemic posed a barrier to response rates during this period, the burden on Dallas County was likely similar for all other counties considered here.

Figure 2: Dallas County 2020 Self-Response Rates by Census Tract and City Service Area

Part of the challenge in completing the Census 2020 questionnaires can be traced to the reliance that the Census Bureau placed on using an online survey as their major data collection strategy. In past censuses, the Census Bureau relied primarily on a mail questionnaire, while data collection for the annual American Community Survey has utilized a mixed mode strategy that included mail questionnaires, telephone interviews, personal interviews and online surveys. Not surprisingly, Black and Latino respondents to the American Community Survey have opted for telephone and personal interviews more often than whites or Asians, while online surveys were the least chosen option.

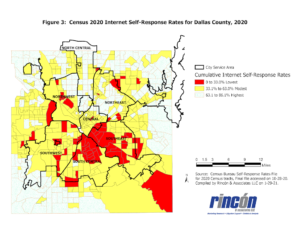

Figure 3 below presents the percentage of Dallas County households that completed the Census 2020 using an online survey. The map presents the cumulative Internet self-response rates for the 2020 Census as of October 28, 2020. Of the seven City Service Areas (CSAs), the Central, Southeast, South Central, Southwest and Northwest CSAs are populated primarily by lower income Blacks and Latinos. It is clear that these CSAs included census tracts (highlighted in red) with the lowest online response rates, while the numerous other census tracts (highlighted in yellow) showed modest online response rates. The highest online return rates were realized for census tracts in the northeast and north central CSAs that were populated primarily by white, higher-income residents.

Throughout 2020, public officials in Dallas County and City of Dallas were aware of the poor performance of the Internet to encourage poor Blacks and Latinos to complete the 2020 Census. Why then was the Internet the main vehicle used for communications related to COVID-19 vaccine awareness, registration and distribution? Good research and multicultural expertise would have been beneficial to decision makers during this period.

Based on my past 45 years of experience in conducting surveys of multicultural populations, it is my opinion that the Census 2020 Campaign sponsored by Dallas County and City of Dallas was not guided by the best expertise regarding the strategies for successfully engaging multicultural population segments in surveys and the biennial census. If it had been, Dallas County might have experienced a higher ranking in Census self-response rates in comparison to the many Texas counties that did not allocate any funding for a Census 2020 campaign.

The challenges facing public officials to ensure a satisfactory quality of life for all community residents have become more complex and will require careful planning using the best expertise in understanding and engaging culturally and linguistically diverse communities. Public officials must resist the temptation to take the path of least resistance by overlooking or dismissing the need for solid research to guide decisions that impact the quality of life of multicultural residents. Dallas County and City of Dallas public officials learned the hard way that engaging culturally and linguistically diverse residents is a complex task that requires multicultural expertise and support from community organizations. As the population of urban areas like Dallas County continues to grow and evolve demographically, the challenges to respond more effectively to important community needs and events will become more challenging. Let’s hope that public officials will be better prepared to respond.

Reference Notes

[1] Garcia, N. and Jimenez, J. (2021, Jan. 28). White Dallas residents outpace Blacks, Hispanics in registering for COVID vaccine. Dallas Morning News, Accessed at: https://www.dallasnews.com/news/public-health/2021/01/29/white-dallas-residents-outpace-blacks-hispanics-in-registering-for-covid-vaccine/

[2] Choi, J. (2021, Jan. 21). Texas threatened to reduce vaccine supply to Dallas County over plan to focus on ‘vulnerable’ ZIP codes. The Hill. Accessed at: https://thehill.com/homenews/state-watch/535294-texas-threatened-to-reduce-vaccine-supply-to-dallas-county-over-plan-to

[3]National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (2020). Framework for equitable allocation of COVID-19 vaccine. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

[4] Rincón, E.T. and Tiwari, C. (2020, March 23). Demand metric for supermarket site selection:

A case study. Papers in Applied Geography, Accessed at: https://doi.org/10.1080/23754931.2020.1712555